What happened to the future?

We invest in smart people solving difficult problems, often difficult scientific or engineering problems.

Here’s why.

We invest in smart people solving difficult problems, often difficult scientific or engineering problems.

Here’s why.

Introduction

Introduction

The Problem

We have two primary and related interests:

- Finding ways to support technological development (technology is the fundamental driver of growth in the industrialized world).

- Earning outstanding returns for our investors. 1

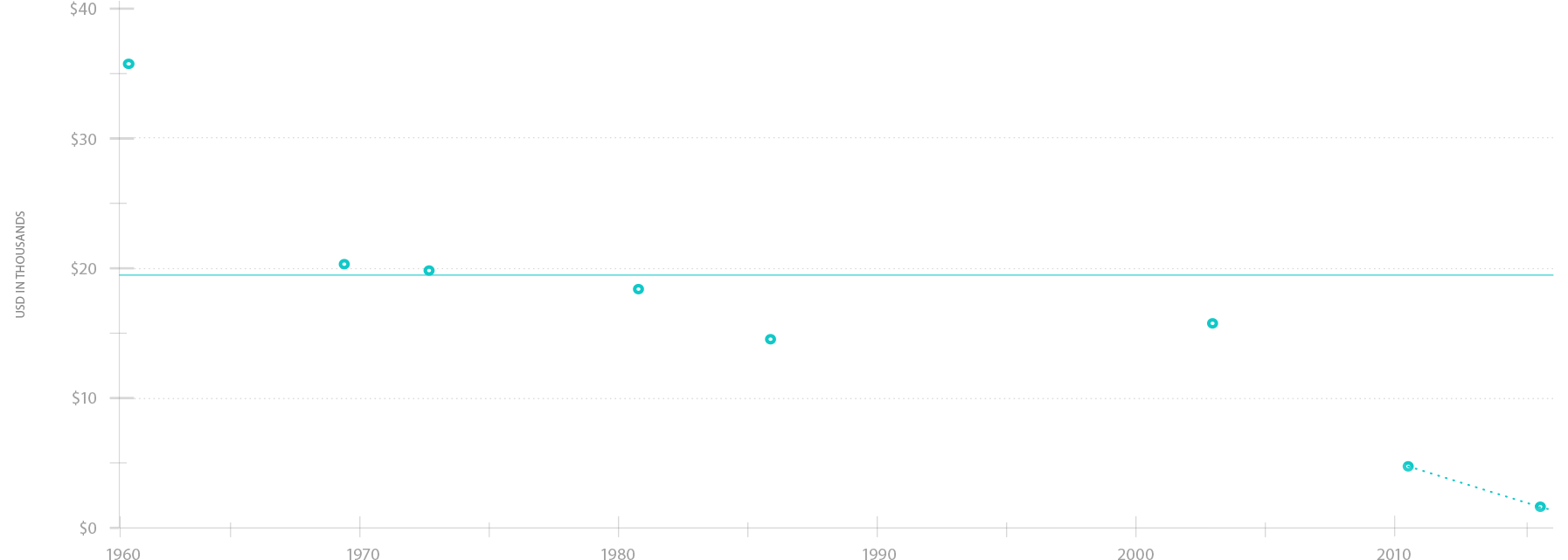

From the 1960s through the 1990s, venture capital was an excellent way to pursue these twin interests. From 1999 through the present, the industry has posted negative mean and median returns, with only a handful of funds having done very well. What happened?

VC’s Long Nightmare

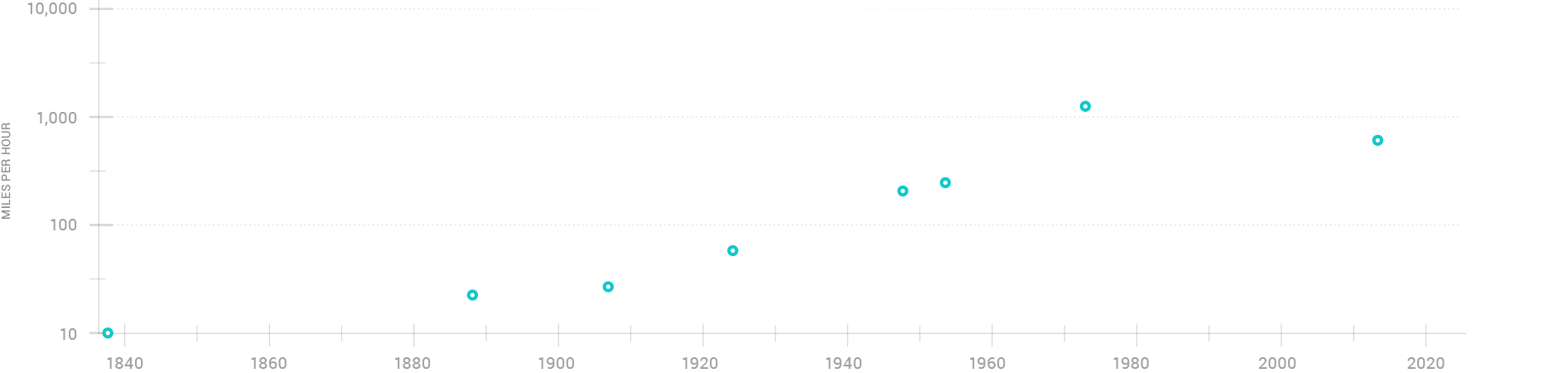

To understand why VC has done so poorly, it helps to approach the future through the lens of VC portfolios during the industry’s heyday, comparing past portfolios to portfolios as they exist today. In the 1960s, venture closely associated with the emerging semiconductor industry (Intel, e.g., was one of the first – and is still one of the greatest – VC investments).

Although success now makes these investments seem blandly sensible, even obvious, the industries and companies backed by venture were actually extraordinarily ambitious for their eras.

In the 1970s, computer hardware and software companies received funding; the 1980s brought the first waves of biotech, mobility, and networking companies; and the 1990s added the Internet in its various guises. Although success now makes these investments seem blandly sensible, even obvious, the industries and companies backed by venture were actually extraordinarily ambitious for their eras. Although all seemed at least possible, there was no guarantee that any of these technologies could be developed successfully or turned into highly profitable businesses.

When H-P developed the pocket calculator in 1967, even H-P itself had serious doubts about the product’s commercial viability and only intervention by the founders saved the calculator.

Later, when the heads of major computing corporations (IBM, DEC) openly questioned whether any individual would ever want or need a computer – or even that computers themselves would be smaller than a VW – investment in companies like Microsoft and Apple in the mid-1970s seemed fairly bold. In 1976, when Genentech launched, the field of recombinant DNA technology was less than five years old and no established player expected that insulin or human growth hormone could be cloned or commercially manufactured, much less by a start-up. But VCs backed all these enterprises, in the hope of profiting from a wildly more advanced future. And in exchange for that hope of profit, VC took genuine risks on technological development.